The sixth mass extinction doesn't politely tap us on the shoulder— it lurks in the shadows enveloping species after species, ecosystem after ecosystem. This, fastest die-off ever recorded, demands a keisaku, a Buddhist stick designed to break through our collective ecological sleepwalk.

In traditional zendos, this wooden stick hangs on the wall.

Its purpose?

To wake up dozing meditators with a sharp strike on the shoulder, stimulating acupressure points that focus the mind and rouse energy. Brought from China to Japan by masters like Eisai (1141–1215CE) and Dogen (1200–1253CE), this “awakening stick” isn't meant to punish but to help.

Fear and grieving are essential experiences on the path to waking up to our current ecological context in its fullness. If we're lucky, that fear hits us like a keisaku stick and motivates us to organize in ways that honor the only planet that gives us life.

Take a moment here.

Maybe a sip of tea or a deep breath before bringing a favorite nature place to mind.

Remember the good times there, bring the details into your awareness.

What does it look like?

What do you feel when you’re there?

Remember the sense of connection; maybe it’s with other people you’ve shared this place with or maybe with the animals or plants that live there.

Do you love this place?

Do you long for this place to be safe and protected?

What if it were destroyed?

How would you feel then?

Many people’s favorite places, many people’s favorite plants and animals are disappearing across the globe.

Bring this place of yours back into awareness and smile, be thankful you have a connection with this place and that it still exists.

And ponder this final question:

How far would you go to save it from destruction?

In trauma work, there's a delicate threshold between creating necessary urgency or confrontation and overwhelming the nervous system, which can lead to freeze or collapse. I often find myself in a dilemma when raising this topic. Similar to my one on one work, defenses emerge when we get close to something precious.

Not just empowerment, but agency plays a central role— how can we regain agency without feeling burdened by guilt or overwhelm?

Community engagement is a powerful tool for building resilience while sustaining momentum for ecological action. In many zendos, monks will “gasho” or hold up “prayer hands” and bow to invite the sacred slap of keisaku.

Unlike these courageous monks, our culture doesn't bow to invite awakening. We prefer the sweet comfortable slumber of modernity. When things like bows or strikes are mentioned they are quickly relegated to the politically incorrect.

Instead, we grow numb scrolling past headlines about warming oceans, record wildfires and melting ice caps, dissociated from reality. Even the most progressive governments repeat empty phrases like “green initiatives” until they've lost all meaning— becoming background noise emptied of integrity and urgency— too big to confront honestly, so exploited or denied altogether.

Facts and figures aren't working. How about something more direct? A transmission perhaps?

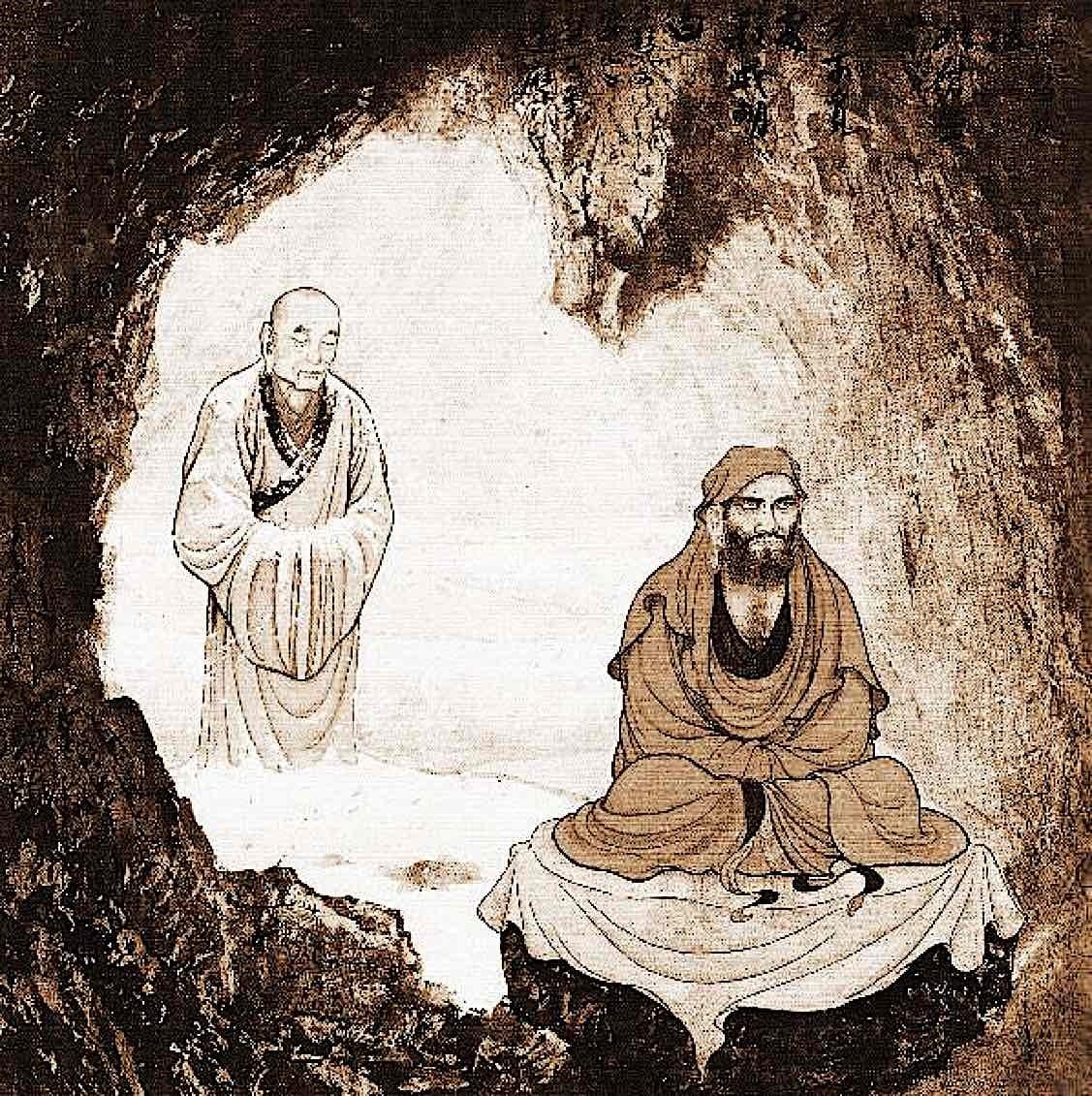

During my time as a student at Naropa University, I learned of its namesake: Naropa (1016-1100CE), the brilliant scholar who became abbot of Nalanda University, the most prestigious University in India flourishing from 500-1300CE. Despite mastering every philosophical text, Naropa recognized the emptiness of his intellectualism when challenged by a dakini: “You understand the words, but not their meanings.” This led him to seek Tilopa (988-1069CE), a master who had renounced monastic life to work as a humble sesame seed grinder.

After enduring twelve trials designed to break through his conceptual mind, Naropa experienced critical transmission. One day, when Naropa offered Tilopa his sandals, Tilopa struck him across the face with one. Upon awakening from unconsciousness, something fundamental had shifted— Naropa experienced direct realization beyond intellectual comprehension. In that moment, he was enlightened.

Genuine transformation often requires direct experiences that bypass our intellectual shields entirely— a hallmark of somatic trauma work.

Obviously, this isn't about violence. It's about the power of direct experience to wake us up. Living life at arm’s length or living disconnected from our bodies leaves us impotent and asleep. Our ecological crisis needs this kind of collective awakening.

When most people first stand at the edge of a clear-cut forest or witness, for the first time, coral reefs converted from vibrant underwater cities to bleached graveyards, something cuts through their intellectual shields. Those who have lived through severe weather events know— these direct transmissions will come more frequently as ecological systems continue to unravel.

We've become too polite about extinction. We discuss “environmental challenges” as if we're talking about a minor inconvenience. Something we’ll get to later, like that screen door that’s squeaked since the 90’s or the gutters that haven’t been cleaned in years. Real hope can only emerge after we've allowed ourselves to feel the gravity of what's happening and it’s ramifications. Unlike the squeaky door, putting this off has existential impacts.

When grief breaks through our numbness, a different relationship with the living world becomes possible. We stop talking about “saving the planet” as some abstract project and begin healing our relationship with the community of life we are embedded within. We realize the inner work we must do to meet this moment and start making decisions that consider the next 7 generations.

Can we allow ourselves to experience what's happening directly, without the filters of greenwashed rhetoric and waiting for someone else to do it?

This path of regeneration isn't comfortable.

But real transformation rarely comes any other way.

The wake-up stick hangs on each of our walls.

Our sandals are right there on our feet.

Can we bow and take the sacred slap that might finally wake us all up before it’s too late?

Whether you felt the keisaku of ecological awakening decades ago or just this morning, what matters is now. With environmental protections being dismantled, this moment demands collective action— neighborhood by neighborhood, watershed by watershed, bioregion by bioregion. The evolutionary bottleneck we face requires all hands on deck and all keisaku sticks in hand.

Bowing,

Patrick

References

Bodiford, W. M. (2008). Soto Zen in medieval Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

Dumoulin, H. (2005). Zen Buddhism: A history (J. W. Heisig & P. Knitter, Trans.). World Wisdom Books.

Goldfarb, B. (2018). Eager: The surprising, secret life of beavers and why they matter. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Guenther, H. V. (1999). The life and teaching of Naropa. Shambhala Publications.

Simmer-Brown, J. (2002). Dakini's warm breath: The feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Shambhala Publications.

Torricelli, F., & Naga, S. (1995). The life of the Mahasiddha Tilopa. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.